Working from home, suddenly becoming your children’s teacher overnight, being furloughed, worrying about your job or your finances, it’s all very stressful. If you’re feeling uncertain and exhausted, you aren’t the only one. If you were tired, stressed, and overwhelmed before, these trying times will only make things worse. The trials and tribulations stress your adrenal glands. While people commonly refer to overworking these glands as “adrenal fatigue”, the more correct term is HPA axis dysfunction. Everyone will agree that stress levels are at an all-time high. The stress in 2020 has been unrelenting. People are burning out. Your adrenal glands and HPA axis are major players in how well you cope with all of this.

Adrenal Overload Symptoms

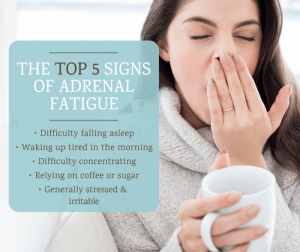

Here are common symptoms of “adrenal fatigue” or HPA axis dysfunction:

- You wake up feeling tired. Even after you have had a full 8 hours of sleep. Sometimes you have even had 9 or 10 hours of sleep and still feel tired.

- You have difficulty focusing or concentrating on one task for very long.

- Getting to sleep and staying asleep is difficult.

- You wake up sweating during the night.

- You find yourself relying on coffee and craving sugary treats to get through the day.

- Relaxing with your friends or family in the evenings isn’t happening.

- Your libido has tanked.

- You notice yourself frequently feeling irritable, anxious, and stressed.

- Your blood pressure is either too high or too low.

- You experience heart palpitations.

- You can’t go long stretches without eating or you’ll get weak, shaky, dizzy, irritable, nauseous, headachey, or light-headed.

Does any or all of this sound familiar?

Without support, you’re going to be in this continuous cycle of lather, rinse, repeat. Whether you want to call it adrenal fatigue, adrenal dysregulation, HPA axis dysfunction, or increased allostatic load, what do labels matter when your quality of life is suffering like this?

Let’s get to know your adrenal glands. That will help us to identify what exactly is happening during adrenal fatigue and what can you do about it.

You Were Engineered for Physical Danger

What’s the key to understanding where our adrenals fit into how we handle stress? Evolution.

Our bodies are a bit of an out-dated model. They were engineered for a world that no longer exists. Back in prehistoric times, we humans were very vulnerable to predators that were stronger, faster, or bigger than us. Think saber-toothed tiger, giant hyenas, giant bears, and human-eating crocodiles. If we saw one of these monsters coming our way, we had to instantly be ready to either fight it off (fight) or run away (flight). This ‘fight or flight’ response is literally designed to save our lives.

These days there are fewer physical predators to run from, but threats are still ever-present, just in different forms. Because evolution hasn’t caught up to the mental and emotional threats that we actually face, our body reacts to these “emotional” threats the same way that it reacts to physical danger. In other words, the exact same stress response is triggered whether you’re running from a tiger or reading a critical email from your boss.

Your Adrenal Glands in Action

So what actually happens in your body when a stressor (physical or emotional) hits? How do your adrenal glands respond to get you through the danger?

Let’s say you have a big work assignment that is due next week, and all seems to be going well. Suddenly an email hits your inbox from your boss. Your deadline just got moved up 4 days. You now have only 3 days to finish a project that you thought you had 7 days to complete. You had those 7 days all neatly planned out, including spending some time with your family relaxing. Even before you finish reading his/her email you notice that:

- Your breathing is fast and shallow

- Your heart is pounding

- Your muscles, especially in your neck and shoulders, tense up

Your HPA Axis Fires Up When Stress Hits

How did all of this happen in mere seconds, without any conscious effort from you to make it happen? Let’s look at that scenario again.

Within seconds of opening that email, your brain identified it as a threat. It then sent the ‘get ready to fight or flee’ instructions to your hypothalamus gland. The hypothalamus is a gland in your brain that directs the pituitary, which then directs the rest of the glands in your body.

Your hypothalamus then sent the super urgent messages directly to your adrenal glands.

That’s why you became a heart-pounding anxious mess in mere seconds.

Your hypothalamus also sent some less urgent messages to your pituitary gland. Your pituitary, in turn, relayed signals to your adrenals glands.

These three glands form a stress-response team, that I referred to previously. It is known as your hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis. It’s the communication network between your brain and your adrenal glands.

Adrenal Gland Function

What messages did your adrenal glands receive?

- Produce hormones (adrenaline, noradrenaline and cortisol amongst others)

- Release them into your bloodstream to get to your muscles and organs like your heart and lungs for them to take the appropriate action.

Your Body’s Response to Your Adrenal Hormones

What actions do these target muscles and organs take when they get their hormonal instructions from the adrenals?

- Redirect blood flow to your heart, limbs and organs like your lungs and away from your digestive tract. More blood flow means more oxygen and nutrients for the tissues and organs that have the highest priority for your survival to work well.

- Increase your heart rate, blood pressure, and blood sugar. This helps to supply oxygen, nutrients, and fuel (sugar) to the rest of your body. This strengthens muscles for fighting or running away.

- Dilate your pupils. Dilated pupils allow more light in to help you see better and expands your field of vision. Typically this happens when you are in the dark or dim lighting. It also happens under stress.

- Expand the airways in your lungs. This allows for a better flow of oxygen in and carbon dioxide waste out.

This all makes sense, right? These lightning-fast processes give us the immediate energy, oxygen and blood flow that we need to fight or flee, and more peripheral vision to see the threats that may surround us.

We Overwork Our HPA Axis

Here’s the thing: this system is built for infrequent, physical emergencies. Now, we mainly use it for frequent, mental, or emotional emergencies. Or, to put it another way, we use it to deal with chronic day-to-day stress. What happens when stress is day in and day out and your adrenals are chronically working overtime?

What Goes Up Must Come Down

When we ask our adrenal glands to produce and secrete their hormones repeatedly over long periods of time, the result is predictable: things get depleted or exhausted. If you’re always speeding, your car is going to run out of gas that much faster. Driving at a more moderate pace sustains your fuel level until you can get to the next gas station and refuel. If we feel threatened or unsafe more often than not, the system that was designed to help us cope can also run out of fuel.

Does Stress Ever Really Subside?

Herein lies the problem with our current lifestyles: when does the threat pass? Or does it ever really pass? Many of us are living under nearly constant low or high-level stress. The signs your body needs to tell it to dial things back may never truly register. So your adrenals are working much more than they were ever intended to do.

This leads to weight gain, exhaustion, brain fog, digestion problems, low sex drive, and a slew of other unpleasant adrenal fatigue symptoms.

It’s Time To Opt Out Of the Constant Fight Or Flight Mode

What can you do to get your body out of the chronic fight or flight cycle and get it back on track?

Identify Your Threat Triggers

The best way to help your adrenals to help you better is to figure out what feels threatening to you. This may seem like a deceptively simple question, but it’s an important one. We may think that we’re pretty chill and only threatened by truly dire life or death situations, but our physiology is saying something quite different.

Keep a Stress Journal

Try this simple exercise: observe yourself for a week to see when you feel your stress response kick in. Note these incidents in your journal (or even just use the Notes app on your phone) along with the details of what triggered it, what time of day, whether you were hungry at the time, how your sleep was the night before and any other factors that may impact your tolerance for stress.

Because this complex chemical response happens instantaneously, before you even think about it, it’s a very accurate indicator of what stresses you out. Do you get stressed when you get a snarky email from a colleague? When you are hashing out finances with your significant other? Having a talk to your child’s principal?

It may not be a physical threat like you nearly got into a car accident. It’s just as likely to be a worry or fearful thought. How many fearful thoughts do you have in a day, an hour, or in the time it took to read this article? Logging them in your journal can help identify what sets you off so you can address the issue or apply calm and rational thought to the situation to come to some resolution.

Learn Your Triggers and Dial ‘Em Down

When you really observe yourself, you may be surprised to see just how often you’re unknowingly flipping into fight or flight mode. The goal is to raise awareness about which situations trigger you, identify your stress response, and learn to dial it back once you recognize that it’s happening.

Adrenal Gland Nutrition

If stress tends to get the better of you, what and when you eat will help. Focus on eating a diet full of leafy green vegetables like kale, spinach, and Swiss Chard. These provide vital adrenal gland nutrients like vitamin B5, B6, C, magnesium, and zinc. Lower your intake of stimulants like sugar and caffeine. These are stimulating to your nervous system, making it harder to remain calm and relaxed.

Adrenal Gland Supplements

Certain natural supplements may help as well, such as:

Schisandra

Schisandra is a Chinese berry that helps your body to handle stress more easily and is also supportive of the female reproductive organs.

Vitamin D

Often taken for its role in supporting a healthy immune system, low levels of vitamin D have been linked to the overproduction of cortisol.

Licorice Root

Licorice has been studied for its role in helping to regulate cortisol and improve energy levels. It’s important to note that licorice can increase blood pressure. So it should not be taken if your blood pressure is already high or if you are on blood pressure medication.

Rhodiola Rosea

Rhodiola is an adaptogenic herb that has been shown to lower cortisol levels when taken twice per day. Make sure that the tea, tincture, or capsule you choose specifies that it is Rhodiola Rosea. Other types of Rhodiola do not have the same research backing.

Get to The Root Cause

These mindfulness-based strategies will help you bring your stress response back into balance, but the reasons why you are feeling reactive may run much deeper. Remember all of those hormones that your adrenal glands work so hard to produce?

A naturopathic doctor with a special interest in hormonal balance can run the right lab tests to check your hormone levels, including your cortisol level. We will work with you to create a personalized adrenal fatigue treatment plan that will move you from a habitual stress response to a more relaxed frame of mind. We can also help you understand how to support your adrenal glands with the nutrients they need to promote your body’s ability to handle stress.

Time to get calm, strong, resilient, and capable of handling whatever problems your day, or the world, throws at you.

By Dr. Pamela Frank, BSc(Hons), Naturopathic Doctor

Adrenal Gland References

Dunlop BW, Wong A. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in PTSD: Pathophysiology and treatment interventions. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;89:361-379.

Dmitrieva NO, Almeida DM, Dmitrieva J, et al. A day-centered approach to modeling cortisol: diurnal cortisol profiles and their associations among U.S. adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(10):2354-2365.

Liao J, Brunner EJ, Kumari M. Is there an association between work stress and diurnal cortisol patterns? Findings from the Whitehall II study. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81020.

Heim C, Ehlert, U, Hellhammer DH. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25(1):1-35.

Buric I, Farias M, Jong J, et al. What Is the Molecular Signature of Mind-Body Interventions? A Systematic Review of Gene Expression Changes Induced by Meditation and Related Practices. Front Immunol. 2017;8:670.

Panossian A, Wikman G. Evidence-based efficacy of adaptogens in fatigue, and molecular mechanisms related to their stress-protective activity. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2009;4(3):198-219.

Orban BO, Routh VH, Levin BE, Berlin JR. Direct effects of recurrent hypoglycaemia on adrenal catecholamine release. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2015;12(1):2‐12. doi:10.1177/1479164114549755

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23832433/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21184804/